You know what? I don’t think I really have a favourite author.

But, off the top of my head, here are some books and authors I hold in extremely high regard:

The Perks of Being a Wallflower – Stephen Chbosky

The Sense of an Ending – Julian Barnes

The Catcher in the Rye – J.D. Salinger

A Moveable Feast – Ernest Hemingway

Lolita – Vladimir Nobokov

A Prayer for Owen Meany – John Irving

J.M. Coetzee

Douglas Coupland

Ian McEwan

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Oh dear. Now I want to go off and read The Perks of Being a Wallflower again.

So, continuing with this increasingly sporadic meme…

So, continuing with this increasingly sporadic meme…

Generally, I consider it quite melodramatic to credit any one single thing as having changed your life. I think life-changing things tend to occur more progressively than that. Yet if I were to suggest that a single work of fiction changed my life, as I am about to do, I would have to bestow that honour upon (This is the last time I include this novel in an answer to this meme, I have just realised I have mentioned it a LOT and that I am dangerously close to preaching.) Douglas Coupland’s Generation X.

I was drawn in by the novel’s fluro-pink cover, which, of course, was Coupland’s intention: attract the masses with a nice bright colour then smack them in the face with the realisation of what they’re doing wrong in their accelerated lives.

It worked.

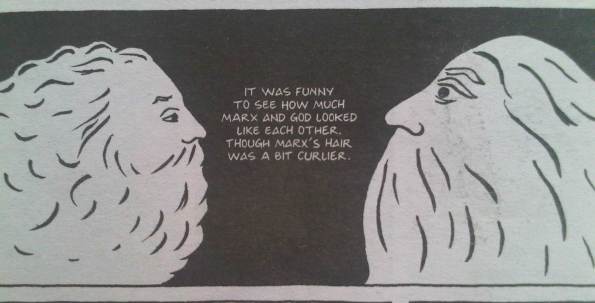

Generation X is one of those books you find yourself returning to, one of those books that you need to return to, when the superficial problems of capitalism and the technological age begin to feel like real problems. We are increasingly subjected to a surplus of information that invades and dominates both our internal and external worlds – sometimes I feel as though I myself am made of pixels, that I can Google where I left my door keys. We exist in a saturated and persepective-less hyperreal world.

The sudden and dominating rise in consumer and media culture has introduced a whole new concept of individuality. Our identities are largely constructed around the attainment of commodities and the maintaining of constructed personalities through social media. Everything has become instant and easy and we no longer have to work for anything, and that is what has come to distinguish our generation from those hardworking, war-influenced generations before us.

The characters of Generation X decide that they don’t want to partake in this hyperreality and so abscond to the Nevada desert in search of a simpler, more meaningful life, and to tell stories to rediscover their humanity and spirituality.

Coupland’s writing is synonymous with the wandering, new-lost generation and is a challenging force in directing our attentions to the changes taking place in contemporary culture and how these changes are affecting our human relationships.

What had the most enduring influence on me is the manner in which the novel exposes the great paradox of consumer ideology; the belief that individuality can be sourced from the accumulation of commodities, when in fact, passive consumption is complicit in the deconstruction of creativity and personal identity. The collapsing of the boundary between high and low culture and the subsequent dominance of mass culture which only allows for individuality within a specific, dumbed-down framework. Coupland’s cutting use of satire really stresses the unimportance and frivolity of modern life when compared with the wholesome immaterial lives and compelling relationships of Andy, Dag and Claire. When money and objects begin to seem too important, when I’ve spent just a little too much time online, I always return to my copy of Generation X to remind me of what life really is about, and that the most valuable experiences can’t be bought.

We shouldn’t feel defined by our careers, by our bank-balance, or how many followers we have on Twitter. Real, valuable life experience is not measured in these ways. And, of course, we all know this, we just need reminding sometimes.

I will leave you with the words of a very wise person, who I think sums up the premise of Generation X better than I ever could:

You have to pay your own electric bill. You have to be kind. You have to give it all you got. You have to find people who love you truly and love them back with the same truth.

But that’s all.

Does Persepolis need a written review? Or do the illustrations speak for themselves?

Maybe I’ll write a review and let the illustrations speak for themselves, I really cannot recommend it enough.

But first I’m going to watch the film, and then I’m going to crack on with reading The Fountainhead, it’s become a very slow process for some reason.

I first picked up this book in the summer. I was in Oxfam Books and it was one of those Oxfam Books that you find in affluent, desirable-postcode towns which means there is actually lots and lots of literature and lots of Booker Prize nominees and such – this one even had a poetry section, which is unheard of in the small town I’m from. So I was in this Oxfam Books, overwhelmed with good quality titles and only 2 pounds in change. There were two Foer novels in the F section, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close and Everything is Illuminated. I had read lots of good things about Foer and about both of these titles so I eeny meeny miney mo-ed and ended up going home with Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close.

I read the first page and resigned it to the bookcase, cursing myself for having chosen another precosiously-narrated, child-perspective narrative over a Julian Barnes or Margaret Atwood.

Then, just after Christmas I heard tell that the film version of Foer’s novel was being released in February. It had Tom Hanks in it and Sandra Bullock and, even though it had a paltry rating of 46 on Metacritic, and Metacritic is the oracle, I really, really wanted to see it. Which meant I would have to read the book first. So I picked it back up again that very day and went to Cafe Nero with it and read and read and read and drank mocha after mocha until I’d finished it a day and a half later. I am so so glad I went back to it.

What about a teakettle? What if the spout opened and closed when the steam came out, so it would become a mouth, and it could whistle pretty melodies, or do Shakespeare, or just crack up with me? I could invent a teakettle that reads in Dad’s voice, so I could fall asleep, or maybe a set of kettles that sings the chorus of ‘Yellow Submarine’.

The novel follows precocious, autistic, 9 year old Oskar Schell after the death of his father in the 9/11 terrorist attacks and his attempts to make sense of the events and losing his dad. Finding a key in an envelope amongst his dad’s things leads Oskar to become an apprentice flaneur of New York city, trailing the streets to visit every address occupied by someone of the name ‘Black’, the name written on the envelope, in the hope of finding the lock the key fits. As Oskar invades the lives of the Blacks upon whose doors he knocks he is offered an insight into the delicacy of human existence and the miscellany of life outside of his own insular world, inadvertently leading Oskar into achieving the worldliness to counteract his constant stream of existentialist philosophy that his dad spent his life trying to teach him.

Sometimes I can hear my bones straining under the weight of all the lives I’m not living.

Yes, autism has been tackled before in literature, and in a similar way (insert The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time comparison here), yet Oskar’s Aspergers is never the main focus of the storyline. In his portrayal of his protagonist Foer transcends literary triteness in his visually absorbing effort and achieves a truly original and beautiful portrait of the mind of a child with apparent Aspergers.

With Foer’s use of photographs, multi-narratives and postmodern graphological acrobatics which dominate the narrative, a strange thing of beauty comes bursting out of all the loss and suffering. It shows its reader what it’s like to love and to suffer and to lose and to hurt, and in this way the novel is alive and active – despite its commentary on death and suffering, it’s living and breathing and reminds the reader that they too are living and breathing, despite all the heart-ache and loneliness that exists in the world. Such devices create a feeling of desperation and angst – an urging to communicate grief and loneliness — that permeates throughout the novel and lingers long after the book has been read.

It has been suggested that art which commentates on 9/11 cannot truly have any real meaning or make any real sense unless it was produced after a certain (indefinable) amount of time after the event. As Extremely Loud was published a mere 4 years after the attacks on the World Trade Centre this perhaps explains some of the negative criticism Foer received to counter his otherwise great acclaim. Yet Foer utilises this apparent lack of perspective which comes with his novel having been written so soon after, in approaching 9/11 from the viewpoint of an innocent, brooding and lost child who – as the novel’s title suggests, has no perspective on the events either, which leaves the reader able to identify with the suffering and sudden loss that attempts to suffocate him.

The novel does, at times, wander into the arena of cloying sentimentality yet it is never quite exaggerated enough to achieve anything other than an immensley strong voice in its protagonist. When a novel is dripping with such topical pathos it is difficult not to identify with its characters, despite any overplayed emotion.

I like to see people reunited, I like to see people run to each other, I like the kissing and the crying, I like the impatience, the stories that the mouth can’t tell fast enough, the ears that aren’t big enough, the eyes that can’t take in all of the change, I like the hugging, the bringing together, the end of missing someone.

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close is a devastating and often hilarious portrait of loss, loneliness, people and the way we live. Through Foer’s rich prose and characterisation emerges a sense of the acute hollowness of life.

I’m interested to see how the visuals of the novel, which rely so heavily on text and the space of the page will translate into film…

I Google’d The Perks of Being a Wallflower right after publishing my last post and look what I found:

The FILM adaptation is being released this year — I don’t know how I didn’t know about this.

Wallflower is one of my favourite books so I’m very much in anticipation of its release. Emma Watson is playing Sam though — thus far, that is my only gripe.

(And yes I did title this post O.M.G. Apparently I say that now.)

Coffee, chocolate, and The Fountainhead.

I’ve only read the first few pages of this one, and I didn’t know a lot about it, or Ayn Rand, going in — except that both have garnered very mixed, and extreme reviews — and I’m not quite sure how I feel about it yet.

I’m almost regretting reading Rand’s introduction to the text, her tone didn’t sit too well with me and I think it’s going to shape the way I read the novel and consider the ideas she presents in it. I’m itching for a bit of philosophy-derived controversy, though, so I’m intrigued to see how it goes! Also, it’s on Charlie’s list in The Perks of Being a Wallflower, sooo…

“I’ve seen you, beauty, and you belong to me now, whoever you are waiting for and if I never see you again, I thought. You belong to me and all Paris belongs to me and I belong to this notebook and this pencil.”

Written as a compilation of vignettes, or stories as Hemingway calls them, A Moveable Feast documents the expatriate lives of the lost generation of literati that congregated in Paris in the 1920s and the illicit lifestyles of the literary and artistic greats of the era: The masochistic, yet charmingly naïve narrative voice of Ernest Hemingway waxes ingenuously, presenting a devourable portrait of F. Scott Fitzgerald ‘s alcoholism and tumultuous marriage to Zelda Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein’s private relationships, T.S. Eliot’s financial misfortunes and Esra Pound’s philanthropism.

Hemingway, though, is careful to suggest that his novel be not read purely as autobiographical – ‘If the reader prefers, this book may be regarded as fiction. But there is always the chance that such a book of fiction may thriw some light on what has been writen as fact.’ – Like every piece of writing, A Moveable Feast is certainly largely constructed and the characters should therefore be read as persona, rather than accurate portrayals of the author’s contemporaries.

Nevertheless, art is always self=reflexive and the novel provides a penetrating portrait of the romantic, early twentieth century literary scene – living on journalism jobs, forgoing food in ordeer to afford to read and write, taking off to Spain and Switzerland and Austria when the fancy arises – the novel exudes romance, albeit a romance perhaps bestowed upon it by twenty-first-century readers nostalgic for the 1920s Parisian artists life.

Yet it is the city which radiates at the novel’s core. The novel has been described as a love letter to Paris, and there is no more perfect a summary than that. Paris is the true hero of A Moveable Feast.

If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.

Of all the gossip that dominates the narrative, it is the relationship between Hemingway and his wife Hadley that really resonates. Their relationship is beautiful, innocent and charming and the reader is left feeling they have invaded a private world:

‘We looked at each other and laughed and then she said one of the secret things …

“How long will it take?”

“Maybe four months to be just the same.”

“Really?”

“Really.”

“Four months more?”

“I think so.”

We sat and she said something secret and I said something secret back.’

The intimate, ambiguous manner in which the two communicate evokes Hemingway’s signature, poetically simple sentences which always contain so much more meaning than is apparent upon first reading.

Much of the novel is comprised of the fictional Hemingway’s thoughts on and experiences of writing. The arduous, demanding, unyielding experience of writing, which only serves in driving Hemingway to more determination to sculpt an identity and prove himself through his craft.

Yet another testament to the in-necessity of length for length’s sake, A Moveable Feast is perfect in it’s brevity. The writing is hilarious, tragic, didactic, both indulgent and tortuous, and is a manifestation of Hemingway’s irrefutable genius.

Caution: I advise not watching Midnight in Paris whilst reading A Moveable Feast, it’s a sure-fire way to give yourself an unfavourable dose of Golden Age Thinking.